Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

In partnership with the Mies van der Rohe Society (Mies Society), Washington Architectural Foundation, and the DC Public Library Foundation, DC Public Library—on the occasion of the Mies building’s 50th anniversary—and the Washington Architectural Foundation were pleased to host a presentation by Dirk Lohan, FAIA, noted Chicago architect, Illinois Institute of Technology Trustee Emeritus, and grandson of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Lohan discussed his personal and professional experiences with the renowned German-American architect, who is regarded as one of the pioneers of modernist architecture. The evening and associated activities were made possible through the generous support of Margaret and David Hensler, Mies Society members.

A guided visit was arranged to the Library of Congress, where over 22,000 photos and pieces of correspondence between Mies, his mother, grandson Dirk, and colleagues—former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (Jackie O), Walter Gropius, Charles and Ray Eames to name a few—reside.

Amongst these letters was correspondence between Mies and Jackie O. Following the assassination of former President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (1917–63), in November of 1963, plans were made to have a library designed and built as a memorial in his honor. Jackie O led the committee and was responsible for the final architect selection for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Mies was amongst the distinguished short list of architects to be considered for this important commission. Meetings were conducted at the Kennedy Compound in Hyannis, Massachusetts and around the world. Other world-renowned candidates included Pietro Belluschi, Lucio Costa, Franco Albini and I.M. Pei, who ultimately won the selection.

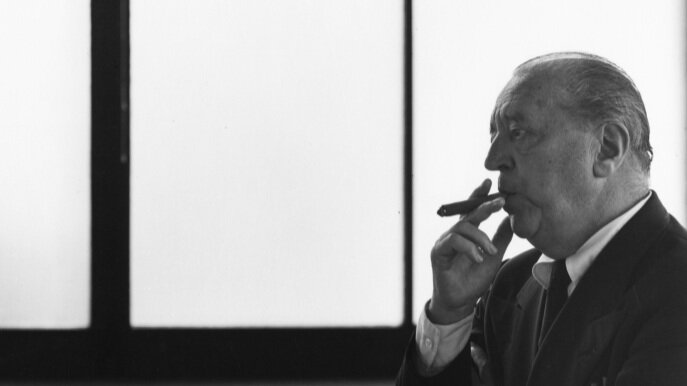

Mies and Jackie O

Photo credit: Getty Images

Although Mies was not chosen for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, this photo reveals a rather proud looking Mies in the good company of former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Boyhood and Bauhaus

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), a German-born architect and educator, is widely acknowledged as one of the 20th century’s greatest architects. He helped define modern architecture by emphasizing open space and revealing the industrial materials used in construction. Born in Aachen, Germany, Mies spent the first half of his career in his native country.

Aachen was a provincial city, but one that looked back upon a glorious past. It had been the capital of Charlemagne’s empire, the first great state in Europe following the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne—better known as the first emperor to rule Western Europe—reigned at the turn of the ninth century, and Mies recalled sitting as a child in the splendid Palatine Chapel—a symbol of the unification of [Western Europe] and its spiritual and political revival under Charlemange—built for the emperor in 800 A.D. by another historically important designer, Odo of Metz, who modeled it after the Byzantine-style church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy [1].

Mies’ early work was mainly residential and he received his first independent commission, the Riehl House (1907), when he was only 20 years old. Mies quickly became a leading figure in the avant-garde life of Berlin and was widely respected in Europe for his innovative structures, including the Barcelona Pavilion (1929). In 1930, he was named director of the Bauhaus, the renowned German school of experimental art and design, which he led until 1933 when he closed the school under pressure from the Nazi Regime.

1Franz Schulze, The Campus Guide, Illinois Institute of Technology, An Architectural Tour by Franz Schulze, with Photographs by Richard Barnes, Foreword by Lew Collens (Princeton Press, New York, 2005), p. 95.

Armour Institute, one of Illinois Institute of Technology’s predecessor institutions, was founded in 1890 just as Chicago was emerging as a center for progressive architectural thought. Men like Burnham and Root, Sullivan and Adler, and William Le Baron Jenney, were transforming the practice and developing an architectural vocabulary that emphasized structure and function over ornamentation. This generation of architects founded what became known as the first Chicago School of architecture—Mies van der Rohe founded the next. In 1936, when Earl Reed resigned as director of the Department of Architecture at Armour Institute, the school engaged Chicago’s architectural leaders in the search for a new director. The search committee, headed by John Holabird, recruited Mies. Mies’ first task was to “rationalize” the architecture curriculum.

When Mies arrived in 1938, he insisted on a back-to-basics approach to education: architecture students must first learn to draw, then gain thorough knowledge of the features and use of the builder’s materials, and finally master the fundamental principles of design and construction. During these early years, Mies held classes in space provided by the Art Institute of Chicago. Mies’ second task was to expand the south side campus. In 1940, Armour Institute and Lewis Institute merged to form Illinois Institute of Technology. Armour Insitute’s original seven acres could not accommodate the combined schools and Mies was encouraged to develop plans for a newly expanded 120-acre campus.

Coming to America

Lasting Legacy

Not since Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia (1819) had an American campus been the work of a single architect. Mies’ original proposal called for a more traditional layout of several large buildings grouped around an open space but in his final Master Plan he embraced Chicago’s rectilinear street grid and designed two symmetrically balanced groups of buildings. Mies’ academic buildings stood in sharp contrast to the patrician campuses of the past. They embodied 20th century methods and materials: steel and concrete frames with curtain walls of brick and glass. The sleek urbanism of Illinois Tech’s campus was a reflection of the university’s technological focus. The Master Plan created an oasis of calm that emulated the openness of the Midwestern prairie in the midst of the chaotic surrounding city. Mies’ buildings are both magisterial and harmonious, and they set a new aesthetic standard for modern architecture. Indeed, Mies’ designs have so pervaded our definition of architecture that it is difficult to imagine how revolutionary the campus was when it was first built.

Mies went on to design some of the nation’s most recognizable skyscrapers, including the Lake Shore Drive Apartments in Chicago and the Seagram Building in New York City.

Whether or not you agree with Mies’ assertation that less is more, his contribution to the modern urban landscape cannot be overlooked. Mies’ architecture has been described as being expressive of the industrial age in the same way that Gothic was expressive of the age of ecclesiasticism. In 1956, famed architect Eero Saarinen spoke at the dedication of Mies’ masterwork, S.R. Crown Hall, and lauded him as Chicago’s third great artist, placing Mies in the prestigious lineage of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. “Great architecture is both universal and individual,” Saarinen said at the dedication, “The universality comes because there is an architecture expressive of its time. But the individuality comes as the expression of one man’s unique combination of faith and honesty and devotion and belief in architecture.” After 20 years as the Director of Architecture at Illinois Tech, Mies resigned in 1958 at the age of 72. In 1959, the Royal Institute of British Architects awarded Mies its Gold Medal and the following year he received the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Gold Medal (AIA’s highest award given). President Lyndon Johnson presented Mies with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963.

It was in 1966 when Mies began suffering from cancer of the esophagus. He died three years later in his adoptive hometown, Chicago. Family surrounded him at his deathbed and at a memorial service in Crown Hall, the general public stood alongside the leading names in architecture to mourn the architect.

Our built environment is meant to be lived in. Mies’ buildings, beyond merely affecting our lives, endow them with greater significance and beauty. His buildings radiate the confidence, rationality, and elegance of their creator and, free of ornamentation and excess, confess the essential elements of our lives. In our time, where there is no limit to excess, Mies’ reductionist approach is as pertinent as ever. As we reduce the distractions and focus on the essential elements of our environment and ourselves, we find they are great, intricate, and beautiful. Less is more.